Hemingway’s Early Life – A Conversation With Hemingway’s Nephew, John Sanford

John E. Sanford is an independent scholar. Through his mother, Marcelline Hemingway Sanford, he is a nephew of Ernest Hemingway. John graduated from Yale University with a major in English literature. He is retired from careers in commercial banking and computer software for banks. John was the editor of At the Hemingways, Centennial Edition, which was published by the University of Idaho Press in March 1999. John has presented papers at several Hemingway conferences and has published articles on various Hemingway topics. As you will read here, John has has a wonderfully adventurous life and is an incredible resource for Hemingway readers.

Finally, John plays a spirited game of bocce ball times a week on three different teams in San Rafael, CA.

AB: You write that your mother Marcelline was motivated to write and publish her book At the Hemingways to correct some of the negative stories Ernest put forth about his family. How did she feel about the book after it was published and how was her book received by family members? What kinds of challenges did editing her book present?

JES: Two questions, two answers. First, my mother was very happy with her book. Part of it was serialized in three issues of the Atlantic Monthly. Almost all of the reviews were generous and supportive. She traveled the US promoting the book and also went on a round-the-world trip with a big promotion in Japan. She loved the stage and was a good speaker there as well as on TV and radio. She loved the publicity and felt for a few moments she was out from under the aura of being merely the older sister of a famous author. She was now a famous author. Strong ego runs deeply in the family.

Second, the biggest challenge my mother faced was the concern she had for sibling’s feelings. My mother was very sensitive to her siblings, one of whom threatened to sue her if anything negative about her appeared in Marcelline’s book. Mother didn’t have much to use as reference material except for her set of the “baby photo books” that her mother (Grace Hall Hemingway) had prepared for each of the six Hemingway children.

She was breaking new ground in Hemingway scholarship and made a few minor factual mistakes. Those that I was aware of, I corrected in the Centennial Edition of At the Hemingwayswhich I edited and had published by the University of Idaho Press in 1999. I know that my mother would be very pleased that her book is still used as principal reference source for the facts of the early years of Ernest Miller Hemingway.

AB: There is wonderful word play and nicknaming going on between Ernest and Marcelline in their letters. The nicknames of themselves and each other are so inventive, playful and creative. Do you know the origins of some of the names that flew back and forth in these letters? For instance, Ivory, Nun Bones, Dearest Old Buzz, The Old Brute, The Antique Brute, Eoints, Mr. E. Monstrocity Hemingway.

JES: That was all before I came into the world. Both my mother and Ernest loved to play with words but Ernest won the prize with his characterization of himself as “Papa.” It is interesting to note that he never used that nickname in writing to my mother.

AB: The friendship between Ernest and Marcelline sings through their early letters. They are each others’ confidants, sharing their thoughts and hopes, swearing each other to secrecy as they write about their hopes and plans. Did your mother talk about her early closeness with Ernest? It must have been a tremendous loss to her when their relationship changed.

JES: As far as I know, they never spoke with each other after their father’s funeral in December 1928. They had a heated confrontation when Ernest arrived in Oak Park after my mother (and father?) made all the arrangements for their father’s funeral. Ernest proclaimed that as the oldest son, he was taking over. I don’t know what ensued after that but there was a fierce religious argument between Marcelline and Ernest when Ernest (a recent convert to Catholicism) proclaimed that their father’s soul was dammed in hell forever for having committed suicide. Marcelline had enough of Ernest’s bullying by then and took him on and tearfully cried that someone as thoughtful, public spirited and self-sacrificing as was Dr. Hemingway was not going to hell. He was going to heaven. (Looking back on what I have learned from letters that are in the library at the University of Texas, it is clear that the confrontation was not about funeral arrangements or religion or heaven or hell, it was about power.) Ernest wanted power; Marcelline didn’t want to give up power. They were both strong willed people only in their twenties. Pow!

Nevertheless, they did correspond for many years and Ernest sent money for Christmas gifts to my mother for my sister, brother and me. When I had a serious eye accident in 1939, Ernest wrote kind words to my mother and express sympathy to me.

AB: Marcelline is very clever and quick witted in her letters. In one of her letters to Ernest, for instance, she describes marriage as being the winter sport of 1919 in Oak Park. Was your mother the same vibrant person throughout her life that she appears to be in her letters?

JES: Like Ernest, Marcelline had periods of elation and depression. When she was up, she was unstoppable; charming, witty and gracious. When she was down, she could hardly get out of bed and we avoided her. She had a strong tendency to over-direct her children.

Since I was the youngest and often ill, I escaped until I was a teenager. Then I recall she would sometimes look at me and say, “You look so much like my younger brother, Leicester. I hope you don’t turn out like him.” At first I didn’t know that was supposed to convey. Later, I got to know Les and I loved him for his charm, his crazy schemes and his, “I don’t give a damn what the world says,” attitude. Years later, when I told Les what my mother said about him, he graciously responded, “Your mother gave a lot of advice. I would have been better off if I had listened to some of it.”

AB: It is obvious that Ernest loved Michigan and the kind of childhood he had there fishing, camping, and hunting. Why do you think he didn’t return more often?

JES: In a book just published, Bay View, An American Idea, by Mary Jane Doerr (The Priscilla Press, Allegan Forest, Michigan 2010) on page 68 there is a quote from one of Ernest’s oldest friends, Irene Gordon, who years later, asked Ernest why he had not returned to the area until August 1947. “He said he was always disappointed when he returned to places he had loved, and didn’t want that to happen here.” I can only add that Hemingway wrote many short stories based on his early years in the area and he had created a fictional world in his own mind. The reality of returning to the original source can be jarring and he preferred his fictional world based on childhood memories.

I too loved this area where I also spent my formative years. The hardest part for me is the friends who have passed away. I feel a bit cheated that we have not had the chance to reminisce about the good times we had as children. Yes, the countryside has changed but Walloon Lake at sunset is still as beautiful as I remember. During the day, the blue-green water is just as bright as the blue-green in the paintings of it by my grandmother (Ernest’s mother) that hang in my home in California. We are all fortunate that my cousin, Ernest Mainland, has restored the Hemingway cottage, Windemere, to its almost original condition and has allowed many visitors tour through the place on special occasions. A board on a wall of Windemere where the heights of the Hemingway children were measured each year is still there along with measurements of my siblings and me when we briefly occupied the place in the 1930s.

(Patrick Hemingway and Ernie Mainland on porch of Windemere, June 3, 2004)

My older brother, Jim, and his talented wife, Marian, have replaced our primitive summer cottage built in 1914 with a proper year-round home. They carefully saved the knotty pine wood paneling from the living room as well as the stones from the fireplace and recreated that room in their basement of their new home. It was a nice touch to our joint memories. I stayed with my brother for a few nights this summer and all the old feeling and memories of my youth flooded my mind.

(The old Sanford cottage on Walloon. The first part was built in 1914.)

I think Ernest missed a great opportunity when he failed to reconnect with Walloon and Petoskey. Who knows, he might have written another story as good “Indian Camp” or “The End of Something.”

AB: Hemingway scholarship continues to grow and evolve. Do you think we will actually learn anything new about Ernest Hemingway or are we simply viewing him from new angles?

JES: I am sure that new material will always be uncovered. Just this summer I became aware of a very important letter that has never been published and may never be published during the owner’s lifetime.

Regarding Hemingway’s work, I believe “each age will write its own books.” The latest issue of the Hemingway Review (Spring 2010) had some absolutely stunning articles about Hemingway’s work including a superb piece by Christopher Loots entitled “The Ma of Hemingway: Interval, Absence and Japanese Esthetics in In Our Time.”

AB: Of course I loved the brief appearance of Hadley in some of Hemingway’s letters. He writes to Marcelline that Hadley will take on the “difficult role of Mrs. Hemingstein.” You have met Hadley – can you tell me about her?

JES: I met Hadley briefly at our home in California in March 1962. She came over for “tea” with her son Jack Hemingway, his wife Puck and their three daughters. (Jack then lived in nearby Mill Valley, CA.) I was struck by how much she reminded me of my grandmother, Grace Hall Hemingway. She had the same “presence.” She was gracious and spoke with almost the same accent. She looked much like how I remembered my grandmother who had been deceased for many years. I was reminded of the oft quoted comment that “men tend to marry women like their mother.” It certainly seemed that’s what Ernest did when he married Hadley.

(Puck Hemingway holding baby Mariel, Hadley Hemingway Mower, Jack Hemingway at John Sanford home in Tiburon, March 1962)

AB: Hemingway’s biographer, Michael Reynolds, initially called Marcelline’s book ,” a whitewash.” What made him change his mind and did he ever speak with your mother about the book?

JES: As far as I know, Mike Reynolds never spoke with my mother. She had been dead many years before Mike started his superb multi-volume biography of Hemingway. I first met Mike at an International Hemingway Conference in Paris in the 1980s. He apologized to me for writing nasty things about my mother’s book.

When I published the Centennial Edition of my mother’s book in 1999, I asked Mike to write an introduction. Even though he was very ill with pancreatic cancer, he wrote a gracious introduction that included an apology for his earlier comments and he also said to me that “he wished he’d had those letters between brother and sister when he wrote his books.” The letters showed a much deeper relationship than any of us knew and showed sides of Hemingway and his sister (my mother, Marcelline) than none of could have guessed.

AB: Did the urge to travel and see the world have any origins in Hemingway’s family?

JES: The Hemingways were early immigrants to America. The earliest records show a Ralph Hemenway in Roxbury, MA (Boston) in about 1630. Most Hemingways in America are descended from Ralph and his wife Elizabeth Hewes. I’d like to know why he left England which was then ruled by Charles I. No doubt he had multiple reasons: religious freedom, land. and opportunity.

Grace Hall Hemingway’s father, Ernest Hall was also an immigrant to America, coming in the 1850s from Sheffield, England. Grace’s maternal grandfather, Alexander Hancock, was a sea captain and part-owner of the three-masted barque, Elizabeth of Bristol. Captain Hancock sailed his ship from England in 1853 to Melbourne, Australia with a load of immigrants seeking gold. Also on board were Hancock’s three young children who had lost their mother in a train accident just days before departure. One of those children was Grace’s mother, Caroline Hancock (Hall) who traveled from Australia to Panama with her father, sister and brother, crossed the isthmus on mule-back and took passage to America. From the East Coast they Hancock family took trains to Dyersville, Iowa where they had a relative and where Captain Hancock “swallowed the hook” and became the town’s postmaster.

(Caroline Hancock (Hall) and her sister Annie Hancock (Roome) just before their departure from England to Australia and America in 1853)

(Captain Alexander Hancock)

When Captain Hancock’s daughter, Caroline, married Ernest Hall, they moved to Chicago. Caroline still felt the pull of the ocean.

(Halls, Hancocks and other relatives at Nantucket, July 24, 1882. Ernest Hall on left, Tyley Hancock on right.)

I don’t know how often the Halls went to Nantucket but I do know that Grace Hall, later Grace Hemingway returned there frequently and took each of her children there for a visit when they turned 11.

(Grace Hall Hemingway and Ernest leaving for Nantucket, August 1910)

Grace’s brother, Leicester Hall became a family legend when he joined the “Klondike Gold Stampede” to Alaska in 1897. His letters home were a travel inspiration to all the family. When Leicester returned from Alaska, he settled in California and Grace visited him in Bishop, CA from time to time. Tyley Hancock, Grace’s uncle, was a traveling salesman in the West and his tall tales also inspired the travel lust in the family. Grace and her father, Ernest Hall traveled together to England in the 1890s before Grace married Clarence Hemingway.

AB: Clarence and Grace Hemingway were such dedicated and intelligent parents who did so much to give their children rich experiences and an extensive education. Did you ever meet them?

JES: Clarence (my grandfather) died before I was born. I did see my grandmother Grace frequently in Detroit, at Walloon and at her homes in Oak Park and River Forest, IL. I idolized her. She was the only grandparent I ever knew and she was a treasure. She had the unique quality of inspiring creativity in me by finding something exciting in everything I did. I still recall some childhood sketches that I brought home from school and her enthusiastic praise for my limited talent. I loved watching her play the piano and listening to her sing in church (the whole congregation would turn around in awe at the power of her voice.) I loved going with her to various museums in Chicago and having her patiently answer my questions about Mastodons, Egyptian mummies or Matisse’s art.

She loved showing me her paintings which covered the walls of her house three levels high. She spoke of her paintings like they were her children. Sometimes she told me about the places where she had painted; Nantucket, the deserts of Arizona, California, northern Michigan, the Carolina mountains and Florida. She had a child-like enjoyment of things like candy and ice-cream cones and she shared those enjoyments with me. When she died in 1951, I refused to go to her funeral with my parents. I just couldn’t bring myself to think of her as dead. I guess I was in deep denial.

(I’ve always felt that Ernest’s nasty words about his mother were just a “cover-up” for his deep love and his belief that she rejected him with her disapproval of the subjects of his writing.) I am reminded of the line from Hamlet, “The lady [gentleman] doth protest too much, methinks.”)

AB: One thing I noticed from the narrative was how quickly the world changed within the generations of the Hemingway family. In the section of letters, Ernest and Marcelline are concerned primarily with their social life and the dances and dates they are planning. Do you think Ernest and Marcelline experienced a “generation gap” (for lack of better word) with their mother and particularly with their father?

JES: Clarence Hemingway (their father) had values that came from his Congregational colonial ancestors. He forbade dancing, drinking, gambling, smoking and probably a lot of other things. Grace Hall Hemingway (their mother) came from a far more liberal background. As mentioned earlier, her maternal grandfather was a ship captain. Her father was born in England and became a cutlery merchant in Chicago. Her father enjoyed the opera, drank and smoked. He loved animals and while deeply religious, he had his own relationship with God. He did not rely on organized church values to rule his life.

Early on, Ernest Hall recognized that his daughter Grace had great musical talent. He encouraged that side of her life and discouraged domestic duties. Grace never was much of a cook. Clarence Hemingway enjoyed cooking and when the family didn’t have a cook, he was the cook. Between the two parents there were very different values. Clarence was a strict disciplinarian and was not above taking his belt or razor strap to his unruly children. Grace was more permissive.

My mother’s book At the Hemingways spells out the different values of the Hemingway parents. Over the years, Clarence had to relax his rules against dancing and even allowed Marcelline and Ernest to take lessons and attend dances. Regarding drinking, my father once told me that a few days before he and my mother were married, they were invited by a neighbor in Oak Park to come over for a drink which they did. Upon their return, Clarence Hemingway berated my father for drinking. My father’s courageous response was, “Dr Hemingway, while we are in your house we follow your rules. When we are not in your house, we follow my rules.”

AB: Ernest was the oldest son in his family and there were undoubtedly great expectations of him. Ernest assumes a paternal role in his correspondence with Marcelline long before his father died. In one letter, written in 1918, he advised his sister, “Don’t marry him but be very nice to him because he likes you a lot.” Where do you suppose this paternal quality came from?

JES: Any answer to this question is pure speculation. However, let me speculate. To start, Ernest was, for most of his formative years, smaller than his older sister, Marcelline. It was only by the time that he was a senior in high school that he was taller than his sister. They were always in competition and often Marcelline who was 18 months older did better than Ernest in school and in school activities. She was editor-in-chief of the school newspaper, he was the sports editor. She was socially adept and had many “beaus”. He was shy with girls and didn’t date. I think that Ernest’s “paternal quality” and his later assumption of the name, “Papa” was to partially compensate for his feelings of inadequacy with his older sister. Much of Ernest’s “machismo” was a cover for his sensitive feminine side.

(Marcelline and Ernest at their high school graduation in 1917)

AB: Did your mother read any Hemingway biographies? And if so, which ones, and what did she think of them? Was she consulted by any biographers such as Carlos Baker?

JES: During my mother’s life time, there were very few biographies. She owned a copy of Charles Fenton’s 1954 Apprenticeship of Ernest Hemingway. (As an aside, Fenton was my freshman English instructor at Yale. Fenton never knew of my relationship to Ernest.) My mother wrote a few notes in the margin having to do with facts but there is no opinion expressed by her. She also wrote some notes in a book Ernest Hemingway, the Man and his Work edited by John K. M. McCaffery which was published in 1950. Those notes related to her defense of Ernest’s writing skills.

Carlos Baker interviewed her twice for his biography of Hemingway but Baker’s book was not published until after her death. I can’t put my hand on it but I remember that my mother made some marginal notes in someone else’s book about the so called “relationship” of Ernest and the Indian girl Prudence (Trudy). Mother said that all that info was bunk. She wrote, “Ernest never had any relationship or love affair with Prudence (Trudy).” Mother told me that Ernest’s “relationship” with Prudence was just a boyhood fantasy. Ernest often claimed that he had Indian blood. According to my mother and to detailed family genealogies, that was just another fantasy.

AB: Hemingway’s financial assistance to his family after the death of his father is admirable, especially at such a young age. Grace seemed to have considerable earning power when she was younger. Was that unusual for a woman at that time?

JES: I have no knowledge of what was usual at that time. Grace did very well with her music and voice lessons. One source has said that she made more money with her lessons than Dr. Hemingway did with his medical practice. That statement seems a bit exaggerated. Maybe in one or two years when Dr. Hemingway was just getting started or maybe, in some years as Dr. Hemingway was always forgetting to send and collect bills and was often paid with chickens and produce from farmers.

AB: I have to say that I kind of admire Grace, although that is an unpopular position. She was dynamic and independent – making furniture, teaching and creating music, painting. Tell me about Grace’s life and how you see her?

JES: See my answer to question 10 (above). I adored her.

AB: Who was Ruth, Grace’s companion later in life?

AB: Ruth Arnold, later Mrs. Harry Meehan, was, as a young girl, a music student of Grace. To help pay for her lessons, she acted as an “au pair” helping Grace with the children. After Ruth married and had a child, her husband died at an early age. Grace took her in to help Ruth’s finances and to provide Grace with assistance in her old age. Ruth stayed with Grace until Grace died. Grace wanted Ruth to have the first choice of a collection of Grace’s paintings.

That large collection of paintings was passed along to Ruth’s daughter, Carol Greene Douglas of Winnetka who has graciously allowed me to photograph them. In February of this year, Carol Douglas died and I have been trying to get in touch with her son who, I have been told, inherited his mother’s home and the Grace Hall Hemingway art collection. Some of those paintings are among the best that Grace painted. I have given presentations of slides of those paintings and others to Hemingway groups in Bimini, Oak Park, Petoskey and Ketchum Idaho. (When I gave a private showing of Grace’s pictures to Ernest’s youngest son, Gregory, in Bimini, Greg was amazed at their quality. Greg shared with me that his father (Ernest) always belittled his mother’s paining skills.)

(Painting by Grace Hall Hemingway of old trees in northern Michigan. In the Meehan/Douglas collection)

AB: Did your family keep the crest that is described on page 108?

JES: Yes, my brother Jim owns it. I believe he has it at his home on Walloon Lake.

AB: Many controversial topics are avoided in Marcelline’s book; particularly Ernest’s friction with his mother in the difficult summer after EH came home from the war. Were there things your mother wanted to write about in her book but didn’t?

JES: She never discussed with me what she didn’t put in her book. I know she left out the names of her sisters when there was something that might be controversial. She wanted to write a positive picture of her family to balance the negative images that Ernest had portrayed in interviews, letters and conversations. As such, she avoided controversial issues and opened her book to Mike Reynolds criticism that “It was a white-wash.”

AB: Ernest’s writing gift shows up early. In 1916, he writes a letter to Marcelline about a fishing trip with his friend, saying:”Lew and I were fishing all night on a pool of the Rapid river 50 miles from no where. Murmuring pines and hemlocks, black still pool, roar of rapids around bend of river, devilish solemn still, dammed poetic.” Did the family recognize Ernest as a good writer? Was that something he aspired to as a teenager?

JES: Ernest showed writing talent early in his life. His mother in particular was very supportive of any creative effort. In the Centennial Edition, among the collected letters, there is a letter from Ernest to Marcelline about her being accepted into the “story club” which apparently involved writing a story. Ernest says, “If I couldn’t write a better story than you I’d consign myself to purgatory. Congratulations.” On it, there is a note in Grace’s handwriting saying “Crazy Nuts, May 5, ’15. Ernest wrote several short stories in high school that were published in the school literary magazine, “The Tabula.” I think both Grace and Clarence were proud of their son’s writing skills. Both parents disapproved about his Ernest’s subject matter. However, Grace, in a lecture note in the 1930s mentioned that she ran across some good stories in the Southwest to send to her son. There is evidence that Ernest wanted to be a writer early on in life. His near-death experience as a 19-year old in WWI intensified that desire.

AB: I sensed a turning point in a letter EH wrote from the hospital in Italy. He tells Marcelline about Milan and says, “I’ve only got one ambition though, but then I better not tell it.” He closes the letter asking, “What do they do anyway besides go to the dances?”, highlighting the difference in their experiences. Just two months later, on November 18, 1918, he tells her, “. . . from long experiences with families, etc., I don’t talk about things anymore. I don’t wear my heart on my sleeve anymore.” And later in the same letter, he says about returning home, “I’m going to work like a dog for I want to make good. Got a lot of reasons to. All kinds of secrets…Nothing definite, but I want to knock them for a loop anyway.” He seems to be turning inward and making plans for his own future. How do you think Hemingway changed during this period and how difficult do you think it was for him to return home after the war?

JES: It is clear that after being in Paris and Italy in WWI that Oak Park looked very tame to him. He had a fantasy of marrying his nurse, Agnes, and returning Europe with her. It wasn’t long after he came back to Oak Park and was still recovering from his wounds that Agnes wrote him a “Dear John” letter. That put him in a deep funk and was the beginning of his wariness of all close love. (Marcelline writes about that in her book.) The next summer in northern Michigan, he had arguments with his mother and she threw him out of Windemere. He never forgave Grace for that but it probably was the shock that he needed to get going with his writing. That fall, he stayed in Petoskey at a rooming house where he wrote with great seriousness. Most of those writings were lost in the “infamous lost suitcase incident” in Paris. That forced him to start over and actually made him a better writer.

AB: Tell me about your mother’s career as a lecturer later in life. Her lectures clearly brought her joy and a sense of independence. What did she lecture about? Where did she travel? And how did she begin this career?

JES: My mother lectured on “The Play Parade and This Season on Broadway”. She would go to NYC two or three times a year and see all the shows, go backstage and talk to the actors and actresses and directors and get all the gossip and put together her show. Her audiences were mainly in women’s clubs all around the country. The era of her act (the early 1950s) was when Broadway was very alive with new theater and before TV was a big factor in entertainment. I saw her show once in Detroit and was amazed at how good she was. She had a photographic memory and could recite dialogue from plays word for word. She also had a talent for meeting people (like her famous brother) and getting them to spill out their guts to her. As a result she had inside information (gossip) about the theater that was not in the press. She loved the travel, the accolades and the applause.

My dad was very supportive and he carried on the domestic duties while my mother was on the road. She, on the other hand, wrote to him almost every day and he responded to the addresses on her itinerary. Despite major temperament and talent differences, they were very devoted to each other. (I have a letter from her to my dad dated August 23, 1951 in which she recalls the evening of August 23, 1922 when my dad proposed to her on a hill overlooking Walloon Lake. I have pasted that letter on the back of a painting by Grace Hall Hemingway of that hill and its view of the beach in front of Windemere and Walloon Lake.)

(Painting by Grace Hall Hemingway of Windemere Beach. It was from this knoll that my father proposed to my mother on August 23, 1922)

Marcelline was always active in the theater. She studied speech at Northwestern University. One of her fellow students was Edgar Bergen who later became famous as the ventriloquist and creator the radio show of “Charlie McCarthy”. Marcelline acted in amateur groups in Detroit and wrote several plays. The most successful was a musical comedy entitled, “Be Seated.” It was spoof of the automobile sit-down strikes turned into a domestic setting involving household help. I can still recall mother and her friend, Dorothy Coolidge, working on the words and music in our dining room and living room. (Dotty later became my sister’s mother-in-law when my sister married Dotty’s son, David Coolidge in 1953.) “Be Seated” was published by the Samuel French organization and mother and Dotty received royalties for many years on productions put on by groups around the country. While the checks were small, the idea that she was getting financial rewards for her creative work was very appealing.

AB: There is a definite pulling away starting with the Key West period – what was going on? He was harsher, and much less affectionate. How much do you think alcohol played a part in his more masculine persona and the devastating letter he wrote to your mother in 1937 about the cottage?

JES: From what I have read, when Ernest met Martha Gellhorn, he was heading to Spain to cover the Spanish civil war. My guess is that the break-up of his second marriage to Pauline, was difficult and induced a great deal of guilt in him. His way of dealing with guilt was to blame others and to drink to forget his problems. He was just looking for anyone with whom to pick a fight. My mother was a convenient target. It is interesting that he later apologized to my mother in a letter dated December 22, 1938. He said his behavior was “rude and boorish.” (This was part of a character pattern for Ernest to strike out at someone and then later apologize.)

AB: Marcelline reaches out many, many times over the years reminding Ernest that they are family, that kindness is all that matters and that they are getting older and life is short. Is there any indication that Ernest took her appeals to heart?

JES: None, except that he kept her letters. Of course, he kept everyone’s letters, even one that I wrote to him during my college days. I was very surprised to find my letter in the Hemingway letters (received) collection at the JFK Library. I don’t know if he read it. I do know he never answered it.

AB: The proceeds of your mother’s book go to the Oak Park Foundation. Can you tell me about the Foundation, their goals and activities?

JES: The Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park was created in 1983 to acquire and restore the house where Ernest and Marcelline and two other sisters were born. Marcelline wrote a detailed description of that house which was never published in her book, At the Hemingways. My siblings and I gave the manuscript to that book to the Foundation to assist its leaders in restoring the “Birth House.” The Foundation also runs a Hemingway Museum in Oak Park that is located in a building that is almost across the street from the “Birth House.” Again, my siblings and I have donated family treasures including books, paintings and furniture to the “House” and to the Museum.

(Hemingway “Birth House” Oak Park, IL)

(Hemingway “Boyhood Home” Oak Park, IL)

In recent years, the Foundation acquired the “Boyhood Home” where the Hemingway family lived after they sold the “Birth House.” The Foundation is restoring the “Boyhood Home” and plans to make it available to the public. The “Boyhood Home” was huge with eight bedrooms, Dr. Hemingway’s office and a music room that was large enough to seat more than 100 people. (The music room was torn down in the 1940s and needs to be rebuilt.) Grace gave musical lessons there, Ernest arranged boxing matches there and when he returned from Italy, Ernest invited a large group of Italian friends to come for a party there.

I saw that house in 1935 when there was a family reunion that included Jack (Bumby) Hemingway and Ursula Hemingway Jepson’s daughter, Gail. My siblings and I are all in a photo with them dated May 31, 1935 with our grandmother, Grace.

I would love to see the music room restored and be there for a chamber music concert in that venue.

(Grace in the music room of “Boyhood Home” with voice student.)

AB: What has it meant to you to be related to EMH? Has it affected the choices you’ve made in life? How about your children?

JES: I think having a famous and creatively accomplished author as an uncle has been an inspiration to me all my life. While my mother highly disapproved of Ernest’s lifestyle, she did admire his writing and his financial success. We rarely heard his name mentioned in our house. Nevertheless, I read about him and as a teenager, I started to read his powerful early short stories. I was very moved by his writing. During college I learned more about his writing and over the years I have read almost all of his books, stories and articles. I have also read many of biographies and literary criticisms. The more I learn, the more impressed I have become of his craftsmanship.

I’ve never wanted to follow in his footsteps as a hunter but his love of travel and good wine and food and good friends has been very appealing to me. (Recently I have learned to shoot a shotgun with blanks when I serve on the race committee of the San Francisco Yacht Club.)

(John Sanford on SFYC race committee boat in September 2008)

When I decided to make a mid-life career change I was inspired to learn more about Ernest’s life and the places he knew by taking a sailing voyage from the Chicago area to San Francisco. My three children were with me for much of that voyage. Since then, I have written several papers and made presentations or attended Hemingway conferences in such places as Paris, Les Sainte Maries in Provence, Key West, Bimini, Sanibel, Havana, Cuba, Sun Valley, Oak Park and Petoskey, MI. Two of my papers and a short story about Ernest have been published. Right now, I am working on a book about my sailing voyage. It has the working title, “The Going Home Voyage: A Hemingway Odyssey.” I plan to have the book ready for publication in early 2012. I also plan to have another paper to present at the 2012 International Hemingway Conference in Bay View, Michigan.

AB: You took your family on an once-in-a-lifetime voyage in 1978-1979. This was a 10,000 mile trip by sailboat which connected you, not only to your children, but to your Hemingway legacy. Can you tell me about the trip, why you decided to take it, how your children remember it, and how it connected you to your family?

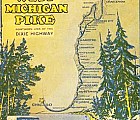

JES: Starting in June 1978, we sailed my 41’ sloop named Going Home from the Chicago area to San Francisco via the Great Lakes, the Erie Canal, and the Hudson River to NYC with a leg up Long Island Sound to Nantucket and back to Manhattan. From NYC we sailed down the Intercoastal Waterway to Florida, then to the Bahamas, Haiti and the Dominican Republic to Puerto Rico. We stopped in most of the Windward and Leeward Islands of the Caribbean to Grenada where we turned the corner and headed to the Dutch Antilles. Next we went to Cartagena, Columbia to Panama and through the Panama Canal to the Pacific. At that point went up the Pacific Coast of Central America to Costa Rica and then Mexico to San Diego and on to San Francisco. We arrived home on July 21, 1979.

(Route of the “Going Home Voyage” 1978-1979)

By coincidence, July 21, 1979 would have been Ernest Hemingway’s 80th birthday. His spirit was with us during the voyage. His younger brother, Leicester Hemingway, in Miami helped me find my vessel and his younger sister, Madeline (Sunny) Hemingway Miller met us in both Charlevoix, Michigan and again in Deerfield Beach, Florida. I was also in contact with Ernest’s youngest sister, Carol Hemingway Gardner, who I visited by land in Garden City, Long Island.

(Leicester Hemingway at his home in Miami in 1978)

When I drove East to start the voyage, I stopped in Dyersville, Iowa and found the grave of Captain Alexander Hancock in a lonely windswept cemetery. I had an imaginary conversation with him and felt as if his spirit was also with me at many difficult places during the voyage. My children and I stopped in Oak Park to visit the two Hemingway homes before we started our trip. When we were in New England, my eldest son and I visited several towns and where the Hemingways and Sanfords settled in the early 1600’s including Milford, New Haven, Branford, East Haven, Terryville and East Plymouth, CT. In each of those towns we found Sanford and Hemingway graves.

I took my eldest son on a tour of Yale University where I had been an undergraduate back in 1949-53 and where the first student in 1702 was an ancestor, Jacob Hemenway.

(Plaque at Yale University honoring its first student,

Jacob Heminway in 1702)

We also visited the site (now a parking lot) of an early Sanford home in about 1640 in Milford, Connecticut. (By coincidence, when I was in college, I used to sail small boats out of Milford harbor into Long Island Sound. I had no knowledge of my family heritage.)

(John and Eric at site of Sanford home in 1640)

My children and I didn’t talk much about my Hemingway legacy, we just did it. The children remember best the outrageous characters of both Sunny Hemingway Miller and Leicester Hemingway. (Ernest was just a name that connected us all together.) Since the trip, my children have become aware of Ernest’s writing and history and have sizeable collections of his literature. All my children also have small treasured collections of Grace Hall Hemingway’s paintings.

I took the voyage for three principal reasons: To connect with my family, to connect with my heritage and to connect with myself. I had become too involved in my work as an international banker and felt it was time at age 47 to step back and reassess life. My eldest son at age 18 agreed to take off the year between high school and college and to be my principal crew. My other two children at ages 16 and 10, joined us when they could during school vacations.

I’ve never regretted my decision to take the “Going Home Voyage.” I just hope that my book will convey all the pain and pleasure of that life-changing experience so that my children, grandchildren and their children will be able to fully relate to that voyage.

We survived devastating damage to my yacht in a storm in Wisconsin, a near-drowning in Nantucket Harbor, the loss of our propeller shaft in the Caribbean, a revolution in Grenada and a horrendous hurricane off the west coast of Mexico. When we sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge on July 21, 1979 after 13-months and almost 10,000 miles, we were like Odysseus; we had survived the temptations and terrors of our odyssey. We were home… sailors home from the sea.

(Going Home returning on July 21, 1979)

(Going Home in San Francisco Bay July 21, 1979)

John E. Sanford © November 9, 2010

Another fascinating post Allie, great questions and John gave very interesting answers. Glad to have you back girl! This is one of the best blogs around.

What an enjoyable interview. Thank you, Allie and John, for great questions and answers, respectively. I also liked all of the pictures and appreciated seeing Grace Hemingway’s paintings.

It’s truly a pleasure to see your blogging again, Allie. I missed my Hemingway fix without you;) And thanks to you John for sharing your experiences and insights. Best to the both of you from South America!

Another one knocked out of the park, Allie! Awesome interview with Mr. Sanford. He is a fascinating interview and had many interesting tales of his family. Loved the sailing adventure. I found out things I never knew about Hemingway and his family, especially the early years. Great to see you’re back, Allie.

Great interview. Smashing as always. Glad you’re back,Allie. Thanks to John for some great perspectives. I love Grace’s paintings! They are gorgeous. Would it be cool to have a traveling exhibit of her paintings,and do some history with it of Ernest and his family? Put St. Louis on the list, please!

gary

Bravo Allie!! So glad that you have made your return to your wonderful blog. Please keep them coming. Thank you John for sharing your rich history with us.

Don’t marry him but be nice to him because he likes you.

Gah.

I love that.

I haven’t read Marcelline’s book, but I plan to, especially for the letters.

This interview is fantastic. I’m a little nervous to be on deck. But excited too. Glad you’re back.

Hello Allie, great interview with so much new information about Hem.

The photos are superb – the paintings, too – and your layout is perfect.

Great job and I hope that you are feeling much better.

John:

I believe you have a nephew named David Coolidge. He would be 55+ -, graduated from Grosse Pointe South HS in 1974 and after that I lost track of him. Dave and I went to school and church together and shared a very interesting adventure together when we were 15 yrs. old. Dave carefully planned our hitchhiking route from Ontario up to Newfoundland, back through New England, where I believe we visited Dave’s great aunt, E. Hemingways sister.(?) I do not recall her name and back then (at that young age) it didn’t seem to matter. We stayed in a charming farm house, filled with books, paintings and a piano, which Dave could play like no one I’ve ever known since!

As the years have passed, and I’ve read more Hemingway, my curiousity has grown. If these facts sound at all accurate, and you happen to know how I might be able to reach Dave, please pass this along.

It was great to read John Sanfords memories & stories of growing

up in the Hemingway family. I was fortunate to cross paths with

John in my search for my great Aunt Nevada Belle connection to

his family (she married Ernests Uncle Le icester )

It is so important to pass on these stories for future generations

& to shed light on the Hemingway legacy.

Thank you !

Judith L Butler

Thank you Judith, John’s stories and John himself is a treasure for all of us.What a priviledge it has been to get to know him and hear about his life. I’ll make sure he sees your comment –

Thanks again, Allie

Fascinating site

I live on White Lake, north of Detroit(Highland Twp) in Oakland County

There is a story among the older neighbors that EH once visited the lake and stayed in my neighbors old stone cottage(early 1900s…..) at the then-called Beaumont’s 7 Harbors resort

http://Www.7harbors.org

Is that possible?

Pls say yes!

Thank u in advance for your courtesy

Regards

Martin Drury

3340 Lakeview Drive

Highland, MI 48356

248/756-1795

Hi Martin,

Thank you for your comment. I don’t know the answer to your question, but I sure know who to ask! Let me post this a few places and I’ll get back to you.

All the best, Allie

Hi again Martin,

I posted your question on the Hemingway Society list-serv and posted one of the responses below. You might think about joining the society because often other scholars are more than willing to help you find the information you need. Here is the response, I hope it helps! Allie

Hello, Allie,

I am sorry to be so late in responding to your forward from the blog but my computer has been sick again probably from my exposing it to an insecure network. it almost sounds like a human form of paranoia, doesn’t it? Anyway, Ernest did travel through the Detroit area in early January 1920 on his way to Toronto for employment with the Connables. A letter to his friend from Petoskey, “Dutch” Pailthorp, asked Dutch to find the best “asylum” for him, which could mean a place to spend the night. See volume one of the letters project for the entire letter. My guess is that it is possible, although improbable, that EH may have stopped in Highland Township.

Best wishes,

Jan

Excellent write-up. I definitely love this website. Thanks!|

I’m happy to re-read this and see the photos, especially since John, my father died in October this year.

Thank you.